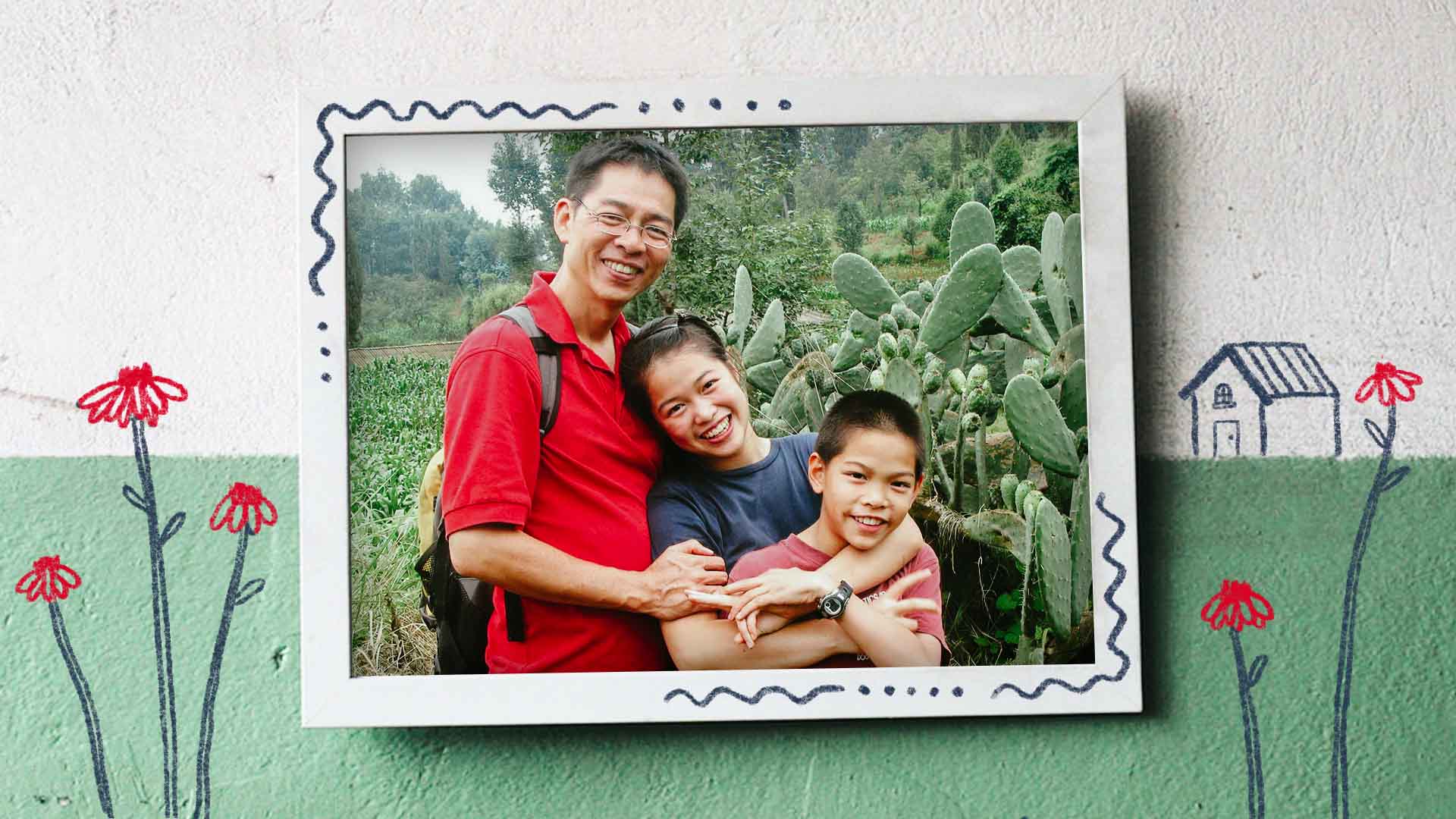

For a while, Dr. Tan Lai Yong and his wife Lay Chin weren’t sure how to respond to the report of their son’s academic performance. At the parent-teacher meeting, they were told that their son’s schoolwork was average.

“Very average,” stressed the teacher.

However, she hastened to add, the secondary school student was attentive in class, ready to engage in discussions, and a “good, kindly boy”.

Lai Yong and Lay Chin exchanged looks. “I guess we’re succeeding, right?” Lai Yong said to his wife with an uncertain laugh.

To their surprise, the teacher seemed to agree.

She explained that while their son’s “mediocre, average work” required the school to alert his parents about it—she took pains to add, “but every teacher reports that we enjoy having him in class.”

Concerned about their son’s grades, Lai Yong asked the teacher if he should engage a tutor.

“No,” replied the teacher, “not until he asks for it.” When Lai Yong asked why, the teacher wisely explained, “Let him fail, he will climb out of it. If you make him go for tuition, he may just remain average.”

Taken aback, Lai Yong asked the teacher, “Can the school take it?”

“Yes,” the teacher replied, “but are you okay with it?”

A Trade-Off Worth Taking

The question encouraged Lai Yong, a missionary doctor who’s now a lecturer at the National University of Singapore, and his wife to continue their approach in raising their two children—especially in Singapore, where the fast-paced society and competitive job market mean that parents are often focused on giving their children the “best ” opportunities for future success.

Amid the emphasis on achievement and performance, Lai Yong is determined not to focus solely on grades.

“Parenting is a process where we all learn about celebrating humility in achievement, maintaining humanity in failure, and giving hope even in tough circumstances,” he says.

“What’s the point of raising a kid who gets all A’s in exams but is frazzled, stressed, and has no spark in his eyes?” he asks rhetorically. “Of course we want our kids to do well in exams, but there’s a trade-off. A bit of light-hearted mischief is sometimes good medicine.”

Parenting is a process where we all learn about celebrating humility in achievement, maintaining humanity in failure, and giving hope even in tough circumstances.

Lai Yong believes in working alongside the Singapore education system (which he admires) to give children a biblical perspective on life goals and coping with success and failure.

“If our kids come in at the top of the class, we bring humility,” he says. “And when they don’t do well, we bring humanity. We help them understand that while the world will rank them, we will not. And we don’t lose hope when there’s failure.”

Humility in Success

Humility, stresses Lai Yong, is not false modesty. It’s about celebrating success with gratitude.

The Bible, he notes, defines humility as such: “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others” (Philippians 2:3–4).

Parents must remind their children that grades reflect their effort, strengths, and potential—but not their worth.

One practical way of showing children what humility looks like, says Lai Yong, is teaching them to be grateful for the source of their success. Parents can do this by being examples themselves.

Parents must remind their children that grades reflect their effort, strengths, and potential—but not their worth.

At work, for instance, the doctor makes it a point to pay tribute to the entire team, even though it is usually the doctors who get the praise.

“We celebrate our achievement but we say ‘thank you’. Send an email, acknowledge others, write a thank-you card. Humility is being grateful for what you have and being gracious in what others don’t have.”

Humanity in Failure

Failure often brings discouragement. That’s why Lai Yong and his wife make it a point to affirm their love and support for their children.

Instead of comparing their kids’ results with those of others, they try to assure them of their own gifts and potential. “That’s our role as parents,” he says.

He believes that parents should not simply echo the pressure that society already places on students, but help their children see a different side to failure and ensure that their self-esteem is not crushed by poor exam results.

His own mother did something similar when Lai Yong gained admission to medical school.

“We don’t always need to give our kids ‘the best’. We teach them what is good and responsible, and sometimes that’s the best.”

While many parents would have quickly made plans for their children to become top doctors and piled on the stress, Lai Yong’s mother, who had no formal schooling and knew that her son was not the strongest academically, reminded him that she did not require him to excel in order to bring her “face”.

“You are my son and always my son,” she told him simply.

That, recalls Lai Yong, was one of the most “liberating and assuring” statements a struggling student could hear. He knew then that her love for him was not dependent on how he did at school, but based simply on the fact that he was her son.

To Lai Yong, his mother’s approach reflected the assurance that God gives all His children in Galatians 4:6–7, reminding us that we are all adopted to sonship in Christ, which is something we cannot earn or lose: “Because you are his sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, the Spirit who calls out, ‘Abba, Father.’ So you are no longer a slave, but God’s child; and since you are his child, God has made you also an heir.”

Hope in Failure

To teach about hope even in the midst of failure, children first have to understand failure, says Lai Yong.

Kids, he says, should not be artificially shielded from the realities of life. For a doctor-missionary who has worked in resource-poor communities, this means helping children understand that life can be tough and failure is real.

“If we deny them the whole understanding of failure, we deny them life,” he says. “We don’t wish them to fail. But if they fail, we bring hope.”

One practical way of teaching children about failure, he says, is being frank about the family’s financial challenges.

“If we deny them the whole understanding of failure, we deny them life,” he says. “We don’t wish them to fail. But if they fail, we bring hope.”

That means explaining family budgets to kids and sharing about monetary limitations, so that children understand what they can have or can’t.

“We don’t always need to give our kids ‘the best’,” he says. “We teach them what is good and responsible, and sometimes that’s the best.”

“I think we should be more open,” he says. “Many people are afraid to tell the children in case they worry or get distracted from their studies. While I don’t think we should burden kids with adult problems, they must know about the issues we face. Then we can thank God for what we have, commit our needs to the Lord, and pray about what we don’t have.”

Indeed, he has seen families in which children grew up “money smart” because they understood how little they had and saw how their parents budgeted—and prayed. “They could see their parents trusting in the Lord,” he adds.

Being Christlike Ourselves

Indeed, parents need to be open about their own challenges because their children are watching closely.

To teach Christlikeness, says Lai Yong, parents have to begin with themselves. Their own behaviour, their own responses to situations, how they treat others, how they apply God’s truths to life—all these will show their children what it really means to be Christlike. “We are fathers, mothers, children together in Christian growth,” he notes.

Adds Lai Yong: “Our kids are looking for authenticity in us. They see what we are doing, how we are living.”

And sometimes, it comes down to the small things.

When the Tans were stationed in Yunnan, China, Lai Yong and his wife set out to relate to their staff and whoever served them in respectful and courteous ways. “We didn’t do anything special,” he stresses. “We just greeted them, we knew their names, we’d share food with them, thank the repairman.”

“Our kids are looking for authenticity in us. They see what we are doing, how we are living.”

He also took pains to make clear to his children the limits of what they could ask the workers to do. “When we had a helper at home, we told them, ‘Ah Yi (auntie) is helping Mummy. She is Mummy’s helper, not your helper. You can’t ask her to wash your plates.’”

Such lessons paid off.

When the Tans left China and the helpers came to say goodbye, he recalls, they complimented him, saying: “Your kids are the only ones who greeted and thanked us.”

Lay Chin and son, camping. Camping is a great way to experience fun and failure, says Lai Yong.

What Kids See

Parents can also send right or wrong messages through their own temperament and behaviour. Lai Yong, who is now the Director for Outreach and Community Engagement and a Resident Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s College of Alice and Peter Tan, often asks students: What unhelpful attitudes or behaviours have you observed in your parents?

In the many seminars he’s conducted, he says, two answers seem to stand out:

One is, “I wish my parents were less anxious.”

While it’s understandable for parents to be anxious about their children’s schoolwork, many kids find that the anxiety gives them unnecessary stress, especially if their parents start comparing them to their siblings or other children. “That anxiety and burden is not helpful,” says Lai Yong. “Children don’t like to be compared.”

The other is, “I wish they were less angry.”

Parents, he has observed, tend to respond to many situations in anger. Parents complain angrily if things go wrong in school or at restaurants. “At home, rather than taking time to find out why a child has done something, we scold or nag,” he notes. “We don’t laugh enough with our kids.”

That anger, he feels, probably arises from an anxiety for the child to do well in school.

Unfortunately, he laments, the anxiety produces anger rather than affirmation.

“At home, rather than taking time to find out why a child has done something, we scold or nag. We don’t laugh enough with our kids.”

Lai Yong points to the many warnings the Bible has about anger. For example, James 1:19–20: “Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires.”

Ultimately, notes Lai Yong, parents teach best not by trotting out rules from the Bible and expecting their children to meet strict standards that they themselves are unable to meet; rather, they bring God’s Word to life for their children through their own behaviours and attitudes towards success and failure.

“As parents, we shouldn’t give standard answers,” he says. “We should pray that we will be able to listen well, give wise answers, and present our children before God.”

Lai Yong’s tips on teaching humility, humanity, and hope:

- Thank God and others for your achievements.

- Learn to be grateful for what you have—and gracious to those who have less than you.

- Grades reflect your efforts, strengths, and weaknesses—but not your worth.

- Remember that you are loved, because God is love.

- Failure is real, and we may struggle. Rely on God, who gives us hope.

Looking for biblical wisdom on navigating your child’s academic rat race? Check out our parenting resource, Help! I’m Stressed About My Child’s Education, today!