Exams are mostly over and soon, the year-end school holidays will be coming round again. That means that our children can finally put away their schoolbooks and do what they like to their heart’s content—whether it’s reading, playing sports, or other hobbies.

Yet, some of us might be feeling a bit less happy to see our children indulging in pastimes that we don’t quite approve of—like video gaming, social media, or bingeing on anime or Netflix shows.

Some of us might even wonder: Is my child addicted?

Parents are often concerned—and rightly so—that their children may have an addiction problem. As a senior school counsellor, I speak to many parents who are concerned about addictions to video gaming, social media, and pornography. For some, the possibility that their children may even have a problem with masturbation or sexting is hard to accept and to deal with.

According to an article by Harvard Health, addiction is defined as:

- Craving for something intensely

- Loss of control over its use

- Continuing involvement with it despite adverse consequences

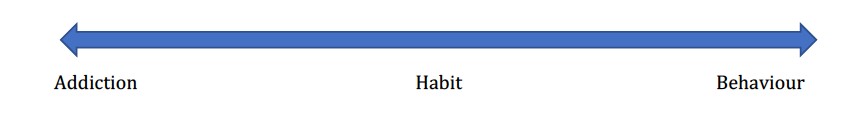

There’s a difference between having an addiction, or simply indulging in a habit or behaviour. For example, just because a child has a video gaming pastime (behaviour) which he spends a fair amount of time on (habit), does not make it an addiction. So, how can we tell whether it’s an addiction or not?

Addiction vs Behaviour and Habits

A child may enjoy an hour or two of video gaming on weekends, or more during the holidays. This could be an activity he simply enjoys or does to pass the time (behaviour).

When this behaviour becomes routine or regular, it is a habit. A habit, notes addiction expert Nicole Schramm-Sapyta, is something we do out of convenience or because it is enjoyable.

In contrast, an addiction is something we do repeatedly, despite causing harm to our lives.

Many teenagers have the habit of turning to social media or video gaming when they are free or bored. It could also be their way of connecting with friends. They are not addicted if they are able to cut down on the activity or stop it altogether when there are negative consequences or responsibilities to fulfil.

Many parents see the symptom of an addiction as the problem, without acknowledging the deeper root cause.

An addict, however, is one who is unable to stop their habit despite harmful consequences.

Many parents try very hard to change their child’s addictive behaviour with what I call the four Cs: correct, cajole, coerce, and command. When these fail, they may then take their child to a counsellor.

Yet, all these tactics are likely to fail, including counselling. This is because parents have failed to scratch where it itches. In other words, many parents see the symptom of an addiction as the problem, without acknowledging the deeper root cause.

Here are two common “itches”, or root causes, for why our children may be addicted:

1. Pain

I once counselled John (not his real name), a teen with an addiction to gaming. He often returned from school to an empty home, and ate his lunch and dinner alone at a food centre nearby before spending the rest of his time alone. Both his parents worked, and were usually not home till after 9 p.m.. As such, they had very little time for him.

Because of this, John felt lonely and unsupported. There wasn’t anyone he could turn to for help when he had difficulty with his homework, which produced anxiety. To cope, he turned to gaming.

John wasn’t hooked on gaming because of its allure; he turned to gaming because the virtual world offered him temporary escape from his anxiety, loneliness, and sense of abandonment by his parents.

A child’s addictive behaviour is often a cry for help. He needs help, compassion, and kind words—not nagging, scolding, or disapproval.

Renowned addiction expert Gabor Maté’s mantra on addiction is: “Ask not why the addiction, but why the pain.” To understand our kids’ addiction, we need to find out what it does for them.

Instead of focusing on our child’s addictive behaviour, look for possible signs of distress, such as sleep problems, social withdrawal, irritability, loss of motivation or interest in studies, lethargy, difficulty concentrating, a sad mood, or changes in appetite.

Is a child’s gaming or drama-bingeing helping them to soothe the pain of loneliness or depression? Is it providing them with an escape from stress or anxiety they’re facing in school or at home?

We can learn from our Lord Jesus, who in His encounters with those who were hurting and struggling with sin, showed gentleness and compassion.

A child’s addictive behaviour is often a cry for help. He needs help, compassion, and kind words—not nagging, scolding, or disapproval. Rather than criticising their behaviour, we need to express our concern with compassion: “I notice you have not been coping well. I am concerned for you. Are you okay? How can I help?”

In this, we can learn from our Lord Jesus, who in His encounters with those who were hurting and struggling with sin, showed gentleness and compassion.

May we model after Him in our care for our children. As Galatians 6:1 urges us: “Brothers and sisters, if someone is caught in a sin, you who live by the Spirit should restore that person gently.”

2. Lack of Connections

Humans were created for connection—with God and with one another. When we bond and connect with others socially and emotionally, we tend to be happier and healthier.

An experiment conducted on rats found that they were less likely to get addicted to heroin when they had the company of other rats and had good living conditions. Those locked up in a cage on their own, however, were more likely to feed their addictions.

A similar observation was made of US soldiers who were addicted to heroin while fighting in the Vietnam War—many of whom miraculously stopped taking drugs when they returned home to families and friends.

The Bible clearly shows us that humans were created for connection. This is why God said: “It is not good for the man to be alone. I will make a helper suitable for him” (Genesis 2:18). Jesus, too, reinforced the importance of connections when He listed “love God” and “love your neighbour” as the greatest commandment (Mark 12:29–31).

Many of us, however, experience brokenness in this world. This can come from personal traumas, social isolation, or defeat and failure in life, which can result in a struggle to bond or connect with others.

Unhealed brokenness will disconnect us from people, and connect us to things.

When this happens, people tend to replace this lack with something else—things that give them some sense of relief. And that’s where some turn to gaming, social media, alcohol, pornography, sex, or other pursuits.

While all of us will experience some form of brokenness in this life, the difference is that some people seek and receive healing for their brokenness, while others continue in their state of brokenness. Unhealed brokenness will disconnect us from people, and connect us to things. Over time, the inability to form meaningful relationships will negatively affect our health and happiness.

It is therefore crucial that we identify our brokenness and seek healing.

Brokenness lies at the centre of all addictive behaviours. Dr. Maté believes that all addictions can be traced to a painful experience, often a childhood trauma. Other possible signs of brokenness are shame, unresolved conflicts, and the inability to form meaningful relationships.

However, before we rush in to fix our children’s brokenness, we would also do well to pause and reflect on whether these same signs are found in our own lives.

When you have received healing for your own brokenness, you will be in a better place to help your child with his.

I have seen cases of children experiencing brokenness because they do not have strong bonding with their parents, or because they have witnessed a disconnect between their parents. When family relationships cause them pain, loneliness, and even trauma, children are likely to turn to other means to soothe themselves.

If you identify a disconnect with your spouse or within your family, seek help. You can’t pour from an empty cup—the first step to helping your child is to first get help for yourself. Some parents find that they benefit from seeking counsel from a church leader, pastor, or family therapist, or from attending a spiritual retreat to reconnect with God.

When you have received healing for your own brokenness, you will be in a better place to help your child with his.

How can you help a child who might be in pain or who might be lacking connections? Here are some ways you can prayerfully consider:

a. Identify ways you can help them to address their pain

- Teach and model healthy ways to cope with stress and anxiety, such as doing physical exercise, having a healthy diet, and using deep breathing techniques.

- Reflect on and lower your expectations for their performance, if this is causing them stress or anxiety.

- Pray with them daily and encourage them with God’s Word, so that they can learn to rely on their heavenly Father for help in times of need (Philippians 4:6).

b. Build your relationship with your children

- Spend more time with them, such as eating and enjoying family activities together. A family who eats and plays together will form strong connections.

- Take time to listen to them without judgment.

- Affirm them instead of criticising them, such as by amplifying their strengths and successes rather than spotlighting their mistakes.

- Be vulnerable, and share your own fear and mistakes. Pastor and author Craig Groeschel said: “We might impress people with our strengths, but we connect with people through our weaknesses.” Ask your kids to pray for you and your struggles.

- If needed, apologise to them for past actions that may have hurt them, and ask for their forgiveness.

If your child’s addictive behaviour persists despite your best efforts to help, consider seeking professional help from established agencies such as the National Addictions Management Service, WE CARE Community Services, or TOUCH Youth Intervention.